“Spring forward, fall back” describes how most Americans deal with keeping time. We will “fall back” one hour from daylight saving time to standard time this year in most states Nov. 5. (Arizona and Hawaii are exceptions. They don’t observe daylight time, so residents don’t need to change their clocks.)

The time change makes news each fall and spring—especially because many people want to abandon the routine. An Oct. 20 Washington Post story (“Daylight saving debate shows there’s no perfect time”), for example, rehashed the pros and cons of daylight saving time.

The story said that since 2019, at least 23 states have tried to abandon the practice of changing clocks each fall and spring. Four have considered remaining on standard time all year. The Uniform Time Act of 1966, which formalized when we change our clocks each year, allows states to choose that option.

Another 19 states want to remain on daylight saving time all year. That move would require Congressional action to change the 1966 law.

The U.S. Senate, with bipartisan support, passed the Sunshine Protection Act in 2022. It would authorize states to choose either permanent standard or daylight time. The House didn’t act on that measure last year. Consequently, the legislation was reintroduced in the Senate this year.

The clock change is not my issue

Those debates are background noise to me. I have no strong opinions about moving clocks back and forth each spring and fall. But the attention to daylight saving time always evokes another strong time-related emotion in me: A visceral annoyance about the westward creep of the Eastern time zone.

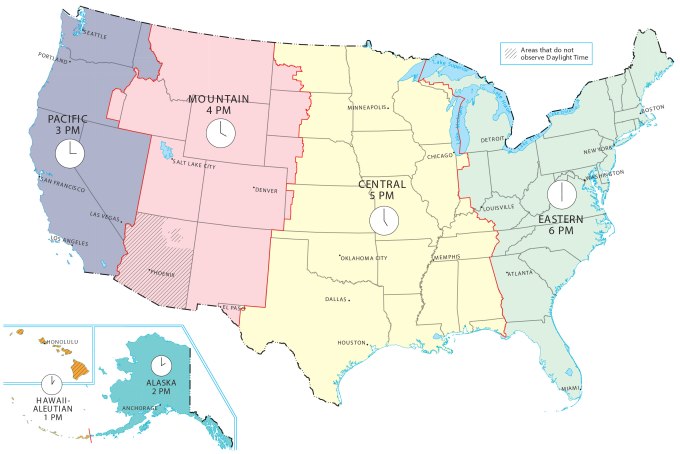

Source: https://gisgeography.com/us-time-zone-map/

I fully acknowledge that my feelings are irrational. No one cares what I think about this topic. Time zone boundaries are not an issue for most people. I cannot influence the situation or what people think about it. Nevertheless, I stew each fall and spring about the current unnatural Eastern time zone boundary. The current time zone map violates my sensibilities.

I was surprised this summer to see in a collection of stories by American humorist James Thurber that he had captured how I feel today in an Oct. 3, 1942, New Yorker article. Thurber described a gathering of journalists in a Columbus, Ohio, restaurant around 1920:

“We would sit around for an hour, drinking coffee, telling stories, drawing pictures on the tablecloth, and giving imitations of the most eminent Ohio political figures of the day, many of whom fanned their soup with their hats but had enough good, old-fashioned horse sense to realize that a proposal to shift clocks in the state from Central to Eastern standard time was directly contrary to the will of the Lord God Almighty and that the supporters of the project would burn in hell.”

The comment was funny in 1942 because Ohio had moved from Central to Eastern time in 1927. I agree, however, with the Ohio political figures Thurber described. That move “was directly contrary to the will of the Lord God Almighty.” Indiana extended the offense to my sensibilities in the 1960s. Indiana moved the Eastern time zone boundary to the middle of the state in 1961 and to the Illinois state line in 1969.

Except for six counties in the northwest corner and another six counties in the southwest corner, Indiana is now on the same time as New York and Washington, not Chicago, the traditional commercial center for the Midwestern agriculture market, of which Indiana is a part. That arrangement doesn’t make sense to me—especially when we consider when the sun rises and sets in Indiana.

Central time originally started much farther east

The Standard Time Act of 1918 originally drew a large Central time zone. The eastern side included portions of western New York and western Pennsylvania; all of Michigan, Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee; most of Georgia, and all of Florida.

Because of when the sun rises and sets throughout the year, I always thought that having all of Michigan, Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee in the Central time zone made sense. Central time coincided more closely with what I considered the natural range of daylight. Of course, policymakers disagreed. They saw some commercial advantage to having all or parts of these states on the same time as New York and Washington. Consequently, the time zone boundary crept west.

Today, the Central time zone boundary runs roughly along the Wisconsin and Illinois state lines (with carve-outs in northwest and southwest Indiana), through western Kentucky and east-central Tennessee, and down the Alabama state line toward the Gulf of Mexico. The Florida Panhandle is mostly in the Central time zone.

Between 1969 and 2006, Indiana compounded the time-zone confusion for me. Like Arizona and Hawaii, Indiana didn’t observe daylight saving time. Consequently, the state appeared to be in the Eastern time zone during the winter and the Central time zone during the summer. Eastern Standard Time is the same as Central Daylight Time from March through October.

October sunrises and sunsets in Indiana and eastern Kentucky are too late for me

In 2006, Indiana decided to observe daylight saving time. I experienced the results of that decision between 2008 and 2010 when my daughter attended graduate school at Indiana State University in Terre Haute. That city sits a few miles east of the Illinois state line. I visited Terre Haute regularly throughout those years. During October—just be for the “fall back” date—the sun would come up after 8 a.m.

My wife and I happened to be in Terre Haute in 2022 on the weekend of the fall time change. The experience annoyed me all over again. The sun rose at 8:21 a.m. and set at 6:45 p.m. EDT Nov. 5. The sun rose at 7:22 a.m. and set at 5:44 p.m. EST Nov. 6. Just a few miles west across the Wabash River in Illinois, the sun rose and set one hour earlier both days in Central time. The Central sunrise and sunset times were more in line, according to my sensibilities, “with the will of the Lord God Almighty” for the rhythm of a late fall day in that part of the world.

Indiana isn’t alone in its daylight irregularities. Kentucky has similar issues, in my opinion. When I was stationed at Fort Knox (1977-1981), I lived in Meade County and worked in Hardin County. Both were in Eastern time. Immediately to the west, Breckinridge and Grayson counties were in the Central time zone.

The original 1918 Central time zone line ran along the Kentucky-West Virginia state line—about 250 miles to the east. Consequently, much as I did in Terre Haute, I experienced many late fall sunrises and sunsets at Fort Knox. They bothered me.

Policymakers have adjusted boundaries for the Mountain and Pacific time zones since 1918, too. Because I have never lived in those time zones, I haven’t thought about the consequences of those changes. But the boundary shifts don’t look as drastic—or as unnatural—as the westward creep of the Eastern time zone.

I can’t shake these thoughts

I don’t know why I can’t get past my exasperation with expanding Eastern time. The emotion has persisted even though I have not lived or worked in Indiana or Kentucky since 1984. Driving trips between Texas and Virginia several times a year since 2010 rekindle my annoyance each time I encounter the time zone boundary farther west in Tennessee than I think is proper. The vexation intensifies at this time of year with each news story or reminder about the coming time change—even though those messages have nothing to do with the time zones. I, nonetheless, think of the folks in Terre Haute who must wait two hours longer than they should for the sun to come up.

In retirement, I have become an even grumpier old man than I was before.

Copyright © 2023 Douglas F. Cannon